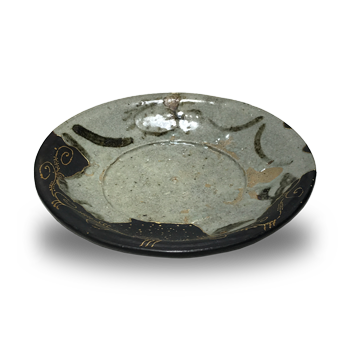

Upon emerging from the kiln, the bowl was immediately discarded and shattered.

It was deemed a flawed piece.

It was never used, not even once.

Exposed to rain and wind, it eventually became buried in the earth.

It slept for four hundred years.

One day, a hoe struck it, bringing it to the surface. It was called a nuisance in the field.

A man picked it up. It was washed for the first time.

When it next awoke, its fragments had been neatly pieced together.

It was gently cradled in a hand.

Everyone treated it with care.

It resolved to live as a tea bowl.

It would live on for a hundred, two hundred years.

Miyauchi Zusho

Kintsugi

Originally, kintsugi refers to the technique of repairing and restoring damaged ceramics, glass, lacquerware, and similar objects. It prevents water leakage and the progression of cracks in fractured areas, fills gaps where fragments are missing, and further involves sprinkling gold powder (shippo) over the repaired sections from an artistic perspective.

Historically, this began with fastening using metal fittings (kasugai). In Japan, lacquer craftsmanship developed early on, becoming so synonymous with “Japan” in Europe that it was often used as a byword for lacquer itself. I believe this led to the development of techniques incorporating lacquer for bonding and coating, followed by the application of gold.

Repairs using colourants to simulate gilding, rather than applying actual gold, were distinguished from kintsugi and termed “kyōsōri” or “kyōshūhō” (joint repair/joint restoration).

Furthermore, gold has long been considered harmless to the body, distinguishing it from other metals. It appears to have been widely used in utensils that come into contact with the mouth, such as those for the tea ceremony and kaiseki cuisine.

This site performs kintsugi using synthetic resin (epoxy resin) – the latest modern technology arrived at through forty years of experience – rather than traditional lacquer (urushi). The technique involves replacing conventional lacquer with resin. Materials such as gold powder (shōko), benigara, and charcoal remain traditional.